6502

December 9th, 2025

In a complete departure from what usually goes on this website, I’ve found myself writing today about 6502 assembly programming.

Almost exactly four years ago, I quit my job as a programmer in Wisconsin (see if you can guess my employer), and found myself stuck in my apartment with nothing to do until the lease ran out in May. I had no real plan at first. When I look over what records I have from that time, I found a bunch of notes from my attempts edit wikipedia and attempts to read “leftist literature.” (Later on I would lose a lot of interest in that stuff, a topic for another time.) Since I no longer had to work, I started drinking massive amounts of energy drinks, so I needed to find something to use that energy on. Somehow it coalesced around programming NES games.

I’d fantasized about programming NES games since I was a kid and had attempted learning 6502 assembly many times before this. It never really stuck though. This time I had the right combination of free time and motivation to actually work through some tutorials, and then make my own miniature dialogue system before I petered out after I ran out of storage space. I’d have to figure out how to use mappers (hardware that moved blocks of storage around into the tiny address space the NES could access). This was where I lost momentum, and instead turned to Algebraic Geometry. I got into the university in China I’d applied for, which gave me even more motivation to study math, and that was that. Six months later I was in Shanghai.

One of the issues I had constantly programming NES games was I didn’t really have a great foundation with assembly programming. I eventually could figure out how to do most things, but only very slowly, and I did everything I could to avoid basic stuff like multiplication by anything but powers of 2, since that would require a non-trivial implementation.

I’d taken a few days off of work to use up what vacation days I have left before the year ends, and I completely failed to write anything during this time. So suddenly on this last day before returning to the office, I was taken over with the sudden urge to program — an urge that often comes to me when I can’t write.

Programming is a thousand times easier than writing, even when I’m working on a difficult problem. I suspect this is because I can put aside my emotions when I program. When I write fiction, I’m trying to evoke feelings and sensation I don’t have the least understanding of through characters that I usually come to hate. That’s not really an issue with programming.

Since I had no idea what I should program, I figured I’d go back to assembly and do some exercises divorced from the NES so I could get a better hang of it. “Why not do Project Euler?” I thought. I’d been introduced to Project Euler by some random internet user back when I first tried programming as an eight year old. “It’s the best way to learn a programming language!” This is advice intended for adults, not children. I think I managed to do the first problem at the time, but certainly not much beyond that. In the two decades since then, I’ve thought about revisiting it from time to time, but never really had the motivation. I don’t really like doing other people’s exercises. I like coming up with challenges of my own. But I was at an impasse, so I figured I’d made an account.

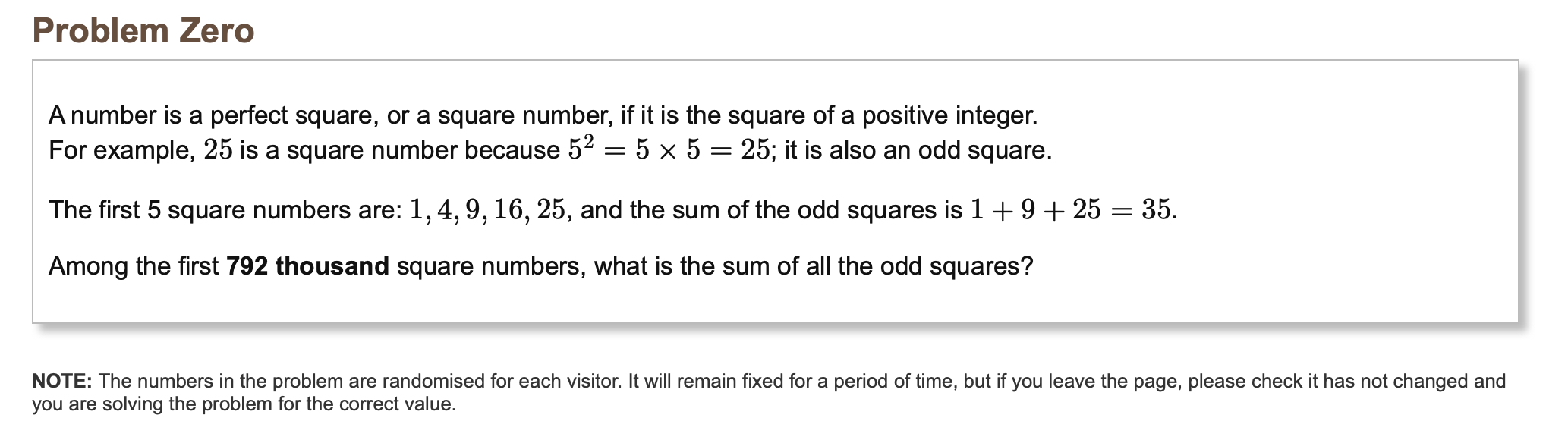

But something seemed to have changed since I last attempted Project Euler. Now there’s a “Problem Zero,” a problem it turned out, that was quite tricky for me to do on the 6502.

(Unfortunately, as you'll soon see, I seemed to have misremembered the number I was supposed to calculate up to.)

The 6502 processor that runs the NES is designed to easily manipulate 8 bits at a time. The largest number you can represent with 8 bits is 255. It’s not that big a deal to manipulate larger numbers, it can just be tedious. As I mentioned above, multiplication is also an issue. The 6502 only has addition and subtraction built in. The sum of squares scales with n^3, and 720,000 ^ 3 is an 18 digit number, so this first Project Euler problem would require me to multiply 64 bit numbers.

So around 1:30 in the afternoon I sat down to figure this out. I used this Javascript-based 6502 emulator I found on the internet just so I wouldn’t have to worry about setting anything up. If I continue down the 6502 rabbit hole, I’ll probably find something fancier to use.

Multiplication it turned out was pretty easy to figure out. I tried doing binary multiplication by hand, which immediately suggested an algorithm. Let A and B be the two numbers I want to multiply, and C the in progress result (which starts as 0). I first check if the “least significant bit” (the bit farthest to the right) of B is one. If it is I add A to C. Then I shift A to the left (multiplying by 2) and B to the right (dividing by 2) and check B’s least significant bit again, repeating the process until B is 0. It turns out that multiplication with binary is even easier than decimal multiplication, since for each digit your only options are 0 or 1, that is, you add nothing to C, or you add A. You don’t have to multiply A by anything (other than adding 0s to the right of it with each step).

So I typed this up in assembly, and to my amazement, it worked perfectly the very first time I tried it. That hardly ever happens. Here’s what the program looks like:

; Multiply 64 bit by 32 bit, store answer as 64bit num

;

;

; Amazingly enough, this worked the very first time I inputed it. That almost never

; happens! I could go out for a peaceful run at 3:00 PM, just as I planned, and have

; plenty of time to appreciate what sunset remained of the day

; $00 - $07 First num, need 64 bit storage but only use first 32 for initial val

LDA #$0A

STA $00

LDA #$00

STA $01

STA $02

STA $03

STA $04

STA $05

STA $06

STA $07

; $08 - $0B Second num

LDA #$05

STA $08

LDA #$00

STA $09

STA $0A

STA $0B

Mult:

; Store our total in $0C -$13

LDA #$00

STA $0C

STA $0D

STA $0E

STA $0F

STA $10

STA $11

STA $12

STA $13

; Check if $08 - $0B is zero

LDX #$00

Loop:

CPX $08

BNE Inner

CPX $09

BNE Inner

CPX $0A

BNE Inner

CPX $0B

BNE Inner

JMP Done

Inner:

; Check if this digit is 1

LSR $0B

ROR $0A

ROR $09

ROR $08

BCC BitShift

; If it is, add what's in $00 - $07 to total

CLC

LDA $0C

ADC $00

STA $0C

LDA $0D

ADC $01

STA $0D

LDA $0E

ADC $02

STA $0E

LDA $0F

ADC $03

STA $0F

LDA $10

ADC $04

STA $10

LDA $11

ADC $05

STA $11

LDA $12

ADC $06

STA $12

LDA $13

ADC $07

STA $13

; Multiply what's in $00 - $07 by 2

BitShift:

ASL $00

ROL $01

ROL $02

ROL $03

ROL $04

ROL $05

ROL $06

ROL $07

JMP Loop

Done:

BRK

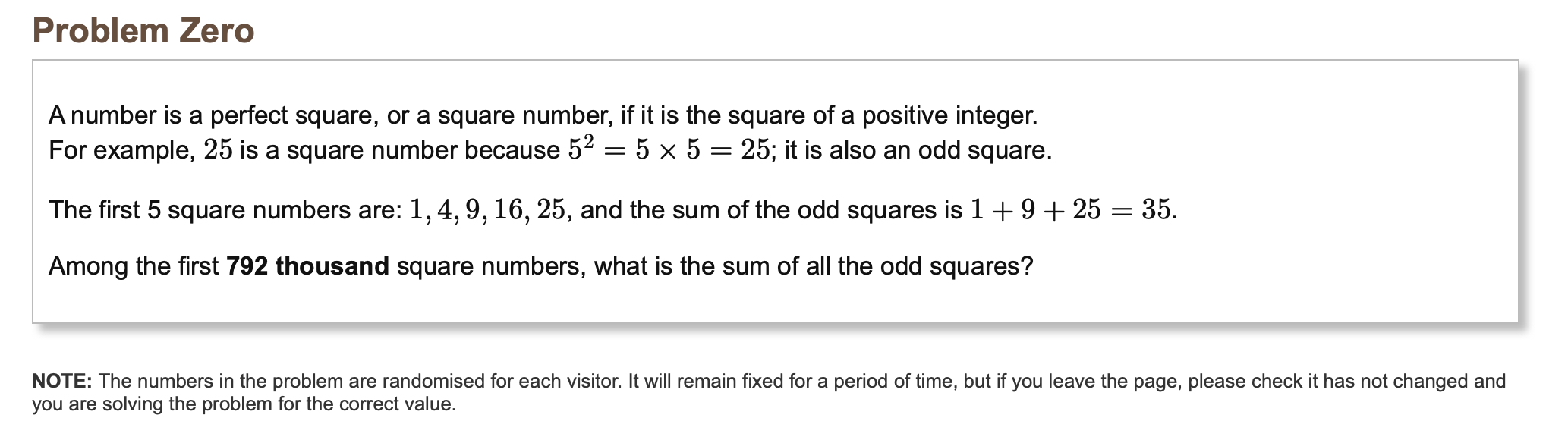

One thing that makes this fun, I suppose, is there’s no real way to “print” my results to a terminal the way I would if I working with a normal programming language. All I can do is check the monitor to see what’s inside the memory locations I’ve chosen to store my answers:

(I ran this on AAAA times BBBB. Notice that AAAA, which was originally in locations $00 and $01, got shifted into $02 and $03.)

This is one of the things I remember liking about NES programming. I’d have to strategically pack the memory I needed in a way that made sense rather than just using variables and having no idea how things are stored, as with higher level programming languages. (With C data structures you do sometimes have to think about how things are stored in memory, but only in a relative sense. I’d never had to have any idea what the absolute memory address of something is.)

I finished my multiplier at 3pm. I went out for a long and aimless run, getting back at 5pm. I cooked the left over dumplings I had from yesterday, took a shower, and filled with confidence I made the modifications necessary to take on Project Euler Problem Zero. This time it took me a little bit of minor debugging to get it working on the example they gave, but that wasn’t much of an issue. I then tested it on the first 2000 squares, and got the right answer, though it took a few seconds. I decided to put my faith in the program and typed 720,000 in hex and let the thing spin.

While it was running, I started taking books off the shelf to pack them into boxes for my move next weekend. I realized I’m going to need a lot more boxes. I took the dog out for a walk, grabbed a bottle of seltzer water from the Lawson and some blueberries from the fruit store next door. I’m suddenly weighed down with memories of doing the same thing three years ago, when I lived in a dorm with my Cambodian roommate. My body heats up after running, which makes the cold air outside feel delightful.

I got back and noticed the program was only 10% done after having run for more than half an hour. It was 8:47 and I have work tomorrow. If I stay up until 2AM, I might be able to confirm if it worked before I go to sleep, but it would be better if I could figure out a different approach that’s faster. Isn’t it precisely for this reason I’m programming in assembly for 50 year old processor? Isn’t this the exact situation I’ve always dreamed of?

I put on Kraftwerk’s Computerwelt. I needed some music about numbers to get me in the right mood to think about this. (Please recommend me more computer music for the next time I need to program -- this is the only computer music I know.)

Of course, I know there’s a closed formula for the sum of odd squares. You can get it from the formula of the sum of squares by taking the sum of squares up to n/2 and multiply it by 4, which gives you the sum of even squares up to n. Then you subtract that away to get the sum of odd squares. This gives (n^3 - n)/6. (Maybe if I’m going to be writing about math, I should learn how to convert latex into HTML.) So if I really wanted to, I could just substitute 720,000 into the formula and be initiated into the world of Project Euler (assuming I didn’t make a mistake). Yet I feel like I should use assembly in some way to get the answer…

If I were to implement the formula in assembly, I’d need division. Division by 2 is not an issue (all you need are bit shifts), so I figured I’d try the dumbest way possible to divide by three: I’d count how many times I could subtract three from (n^3 - n)/2 before I reached a number less than 3. This still took about half an hour to implement due to how tedious it is to type in 6502 assembly involving 64 bit numbers, but once I got it working, I quickly realized that division this way would still take several hours — maybe even more time than my first approach. So what am I to do? I’m too tired to figure out how to divide like an adult (I more or less know how to do it, based on working out binary long-division by hand, but it’s slightly trickier to translate into assembly code than multiplication was). I suppose I’ll just leave my program running and see if it got the right answer when I wake up tomorrow.

And so, my last day before returning to the office has fluttered by, without having anything to show for it. All the nostalgia and wonderful feelings I’d had earlier after walking the dog and drinking seltzer water have dissipated. At least I get to sleep with the knowledge that my computer is hard at work, calculating important numbers…