Before

My Noise Poetry

Last year, around the time I started listening to noise on a regular basis, I had a dream about Junky — the "last surviving member" of Torturing Nurse. In this dream, he was my upstairs neighbor (we all lived in an office building the size of the planet) and had come down to tell me that I wasn't legally permitted to scream. He'd heard me screaming late at night into my pillow. It's not that the noise bothered him — it was simply that the faculty of screaming had been patented in the 50s, and anyone who wanted to scream after that had to purchase a license. In the good old days, maybe we could get away with stomping all over copyright law, but not today — it certainly wouldn't befit anyone with serious artistic aspirations to do so. He was simply being a good Samaritan, warning me before I got in real trouble.

It's hard to say what relation this dream Junky held with the real Junky made of human flesh — this man I'd encountered many times sitting on a plastic stool at the entrance of Trigger, holding a printed out list of everyone who'd bought tickets, crossing each name off when they arrive. Was it a product of my own subconscious? Was it his ghost? Was it really him, taking on supernatural powers in order to impart his wisdom unto me in my sleep? Or was it simply a demon, wearing a Junky mask, just as the real life Junky has worn all sorts of masks?

Not long after I had this dream, I attended A Bunch of Noise (一把噪音), a three day long event at System, one of the largest "underground" venues in Shanghai. Before A Bunch of Noise, the only noise performances I'd seen had been in tiny rooms where an audience of 20 was considered massive.

I'd been to System many times before this — my girlfriend DJed there almost every other week in 2023. Yet I associated it with a completely different sound and crowd than what I'd encountered at the two places I'd seen harsh noise shows in Shanghai: Trigger and Mingshi. When I thought of System, I imagined fashionable people up to date on all the newest trends in street fashion, standing around, nodding their heads or even dancing to dark electronic beats. Would they like noise? This is the question I’m always worrying about. “Will they like it?”

Now, as I write this, System is gone — it closed in January — and this year's A Bunch of Noise will be held at Bandai Namco instead. Being a bit of a jerk, I didn't really like System when it actually existed. As soon as it closed though, I regretted not going there more. There was, admittedly, a good reason I didn't go very often: 9 nights out of 10 were devoted to DJing, so unless my girlfriend was there, it was hard for me to be interested.

The exception to this was at the end of 2023, when I started seeing the name "Suiki" appear in the announcements for events at System. Next to his name was a photograph of an old man with an immaculate mustache. This was Suiki Lor, a master barber who was temporarily residing in Shanghai at the time. He'd been DJing since the 70s in San Francisco, so the legend went. That's the exact sort of thing that inspires my imagination. Whenever you have an old men appear in the midst of a crowd of children, I instantly become a fan, regardless of what the old men are doing. So I kept planning to go see Suiki, but for one reason or another, I was busy every night he played. Then before I knew it, I saw an announcement for his farewell party in January. So I went there by myself. At the time my girlfriend was regularly DJing there, so she could get my name on the guestlist for any event at System, which was somewhat necessary because I didn't have any money — however she insisted the the Suiki farewell party was free. I'm not sure what she was basing this on. When I got there, the lady at the entrance told me my name wasn't on the list. I said "Oh, I thought it was free," and reached for my phone to pay. "Don't worry about it," she said, "we know you." And then she gave me one of the paper wristbands and let me in. That was the one and only time in my entire life I've felt important. I'd never DJed there, I wasn't friends with the management, I'd never done anything worthy of remembering me by — but somehow from my girlfriend putting my name on the guest list enough times, I was turned into a person admitted without her assistance. This was a Wednesday night, so it wasn't like it was very crowded anyway. I walked into the main room, and a lady named Kaleido Jazzlegs was playing 70s soul music on actual vinyl as opposed to the modern digital DJ controllers — "So these are the real DJs," I thought. When Suiki stepped into the room just before midnight, all sorts of people half his age lined up to hug him, and one girl was even crying. I'd worm my way into the farewell party for someone I was only seeing for the first time, and all I could do was wonder what it was like to be one of those people crying.

The reason I was cynical about System at the time was that it seemed too big. It had two floors, a main auditorium with a balcony around it, a pool room on the second floor with a fountain in the shape of a headless naked lady, and a smoke room called the danlu (丹炉 — the (Immortality) Pill Furnace), hidden behind the stairs that led up to the balcony. I always like the danlu better than the main room. During A Bunch of Noise, it's where all the most interesting performances happened. At the center was a hollow pillar, which functioned as a closet where the soundboard was stored. Normally there’d be a DJ controller set up in front of it, but for A Bunch of Noise they had a drum set and guitar amps brought over from Trigger. Emanating from that central pillar was a set of terraced steps doubling as benches — you could sit on them or stand as you pleased. On top of those were big floor-to-ceiling windows that went around the perimeter of the room.

Part of what gave A Bunch of Noise its peculiar atmosphere was that it represented an opportunity to see System during the day. I’d previously only seen it late at night, in the dark. I was so used to coming to the danlu when it was empty of anyone other than a few chainsmokers playing Mahjong while my girlfriend DJed in the main room. I’d stare down at the traffic lights, like green and red blood oozing out of some grotesque polygonal alien creature from a PS1 game, diffusing through the inky black night.

Both days of the main show of A Bunch of Noise started at two in the afternoon. For the first few hours, there weren’t that many audience members — it would gradually fill up as the sun set and the danlu was bathed orange. By night time even the main auditorium was packed. I found this somewhat regrettable, since it seemed to me the best performances all happened early in the afternoon. The night time was for big boisterous spectacles, like sparks flying off of sheet metal and a guy dancing in his underwear, emerging from a uterine sack. These of course had a glamor of their own — but they couldn’t compare with the first act of the festival, Rhythmicshit walking into the room and in the span of 10 minutes filling it up with crumpled newspapers.

Here’s a poem I wrote a few months later about Rhythmicshit:

Bag on your head,

newspapers stained

with your phlegm —

What is this song

you keep on singing?

I had begun trying to turn each of my encounters with noise into poems after I read the Haruki Murakami story "Yakult Swallows Poetry Collection," wherein he reminisces about a (fictional) collection of poems he'd written in his late 20s during baseball games held at the Yakult Swallows home field Jingu Stadium. The Swallows were a terrible team at the time and their stadium was invariably desolate:

I steadily became accustomed to regular loss: “Here we go again — another defeat.” Like a diver carefully takes his time to acclimate to the different water pressure. It’s true that life brings us far more defeats than victories. And real-life wisdom arises not so much from knowing how we might beat someone as from learning how to accept defeat with grace.

“You’ll never understand this advantage we’ve been given!” I often used to shout at the Giants’ cheering section. (Of course I never actually shouted it aloud.)

As I often do when engaging with great literature (please indulge me in considering Murakami "great"), I attached myself to the most superficial aspects of it. "I wish I could be a fan of a losing baseball team," I thought.

At the time, rather than spending my free time in an empty baseball stadium, I was going to Trigger every weekend — a venue for noise and experimental music. It's room 308 of the Lianhe building in Putuo district, right by Caoyang station, about 20 minutes from my house. I don't mean to imply that the noise guys at Trigger are like a losing baseball team, but there is a certain aspect of noise that feels like a "rooting for the underdog" — if you regularly go to noise shows, then sooner or later you'll end up at one where you're the only person who bought a ticket. A video of someone you idolized might have crossed over into "normal people internet", and rather than mesmerizing all who come across it, the average internet user instead vocalizes a visceral collective disgust. Noise seems to lend itself to failure, and so I figured it's as worthy a subject of poetry as any other.

The following three poems about the staff at Trigger might give you a taste of what this exercise amounted to. The first was about Huang Lei, the sampler player of Rhythmicshit and co-founder of Trigger. Over the first few months I encountered him, Huang Lei would have a different hat on each time. A little pointy black cap, a trucker hat with the letters GGG, a blue durag — this is just a small sample of all the hats he's worn. I wrote this poem about one of Huang Lei's solo:

I was looking

for you, hoping to

hear your voice —

but all I found was

microwave popcorn.

He screamed into the microphone, which attached into his magic wire covered wooden box, and through the magic of modular synthesis, it turned into nothing but little popping noises.

I wrote the next one for Junky. Besides performing as Torturing Nursee also does screams for Rhythmicshit:

You smile

as your body turns

to liquid —

a mask floating in

a dark red puddle.

The last of these three poems is about Shu Ride AKA Shu Qi AKA 舒骑, a purveyor of digital vortices of cut-up upside-down samples. He is an expert in wearing colorful trousers.

It was so cold

When my ear touched

against your chest —

white static instead

of a heart beat.

So as I found myself spending three days in System watching noise, my mind naturally tried to reshape what I saw and what I heard into tiny poems.

The second performance was Globe Discount Center in the main auditorium. This would be the general pattern — the crowd would go back and forth between the danlu and the main auditorium, though sometimes two or three performances in a row would be in the danlu, so we'd get to watch the next person set up, not having had a chance to do so preemptively. That would all come later though — GDC was already on the stage when we walked in. He's the other American noise guy in Shanghai besides myself, though I hadn't talked to him yet at the time. His performance consisted of a montage of old television footage of balding men wearing big glasses, old ladies eating hamburgers while being hooked up to electrodes, and serious looking men in suits making speeches that are almost certainly incredibly stupid and meaningless. All of them were white. I thought to myself “this guy is an expert of the weirdness of the white body in all its forms.” I wondered what it meant to display the ugliest and most horrifying aspects of the 20th century white body to an audience of Chinese people deep into the 21st century.

Your body covered

in stranger’s dandruff,

the world they

created crumbles

around you.

Later that day, before guitarist Zhu Songjie's pedal performance, I made friends with another American, Stephanie. Unlike me, she actually had a salary and funds to travel. She had gone to Japan over the Chinese New Year break.

“I wanted to see what Japanese noise was like," Stephanie said. "I bought a ticket ahead of time for a show, but it snowed that day, so I was one of only three people who showed up. I saw an old man rubbing a violin bow against a bird cage. It made me want to become a noise musician. ‘Maybe if I start now, by the time I’m that guy’s age I too can be playing to audiences of up to three people.’ So when I got back to Shanghai I bought a guitar. I told my brother in America about this, but he said it’s already too late. ‘These guys start making noise when they’re twelve. A thirty-year-old can’t just decide one day they’re going to make noise and hope to compete with them.’ So I guess it’s just a pipe dream.”

Not long after this we moved into the main auditorium and stood in the front row to watch Zhao Ziyi. Zhao Ziyi was 16 when he started making noise, not 12, though I suppose the point still stands.

I still didn't know many of the members of the noise community at the time — particularly the Beijing half of it. I'd notice a certain audience member with a distinctive face, a photographer who looked constantly constipated. He'd pushed me and other audience members out of the way countless times in order to capture "the perfect shot." Then at one point, walking into the danlu, I was surprised to find him standing there, donning a bass guitar. He was a musician too, though I never caught his name.

I saw your ghost.

He had no face, only

a drooping hat,

fingers ground to dust

by tight wound steel.

The second day opened with the Shanghai Oscillator Group, whom I'd written about the previous December. That essay was a bit of a fluke. After the performance was over I went to my girlfriend's friend "Sparrow"'s house, about a twenty minute bike ride from Trigger. She lived in the "dark forest", which did in fact get extremely dark at night. There weren't any streetlights. I'd come in through the south entrance, not realizing that she lived by the north entrance, so I had to navigate the winding paths using my phone as a flash light. She lived in her ex-boyfriend's apartment in one of the middle floors of a high rise apartment building — the kind of high rise one finds everywhere in Shanghai. I never figured out what happened to this ex-boyfriend of hers, but his apartment (or rather, former apartment) was quite massive. Shining white floors. Bookcases filled with barbies that Sparrow had collected. There was some other friend over who was an expert in the art of tea drinking and was making everyone try all the tea he'd brung along with him. He was wearing all black and had the kind of haircut a badboy villain in a mid-2000s Taiwanese "dramedy" TV series might have. He poured tea with a flick of the wrist, as though to impress on us that he did in fact know what he was doing. We went downstairs to the mall across the street for dinner at a restaurant that only had meat. I didn't feel like going through the gymnastics necessary to order something vegetarian, so I just said I didn't need to eat. I started thinking about what I'd just watched, two hours earlier. I looked through the notes I'd made on my phone. This was one of those miracle situations where I was trapped with nothing to do in an emotional state conducive to contemplation, so while everyone else ate, I wrote sentence after sentence about my memories of what had happened. I found myself rearranging them until, by the time dinner was over and everyone was going their separate ways home, I had a somewhat coherent sequence of words. This was a bit of a miracle: I'd always found music incredibly difficult to write about. Yet here I was, returning home from my first visit to Trigger, finding that I'd been able to verbalize what I'd experienced.

A week afterwards was Bass Day at the Ming room. This was an event put together by Fish, "the provisional successor of the Ming Room", a goateed art teacher and (former?) bassist of Silencewave. I’ve never seen Silencewave proper play live, though I’ve seen Ding Ding AKA Unitrip, one of its other members, perform with the trumpeter 独行侠 at Sympathy Angel, a bar connected to the underground fashion boutique Terminal 69. There were so many elements introduced over the course that performance: a machine emitting sparks, a juicer, the dismantling of the mic stand, and a shrouded lady appearing half-way through to belly dance, just to name a few. Throughout we were treated to Dingding's manifold vocalizations. Her screams or gasps or shrieks (I'm not sure which word is most appropriate) came out in tiny discrete pulses, like a Geiger counter held up inches from a block of green glowing uranium. I wanted to scream like that.

Icy clouds of smoke

emerged from your mouth,

too heavy

to be dispersed

by the wind.

On Bass Day, Fish had invited Zhao Ziyi, the 17-year-old from Beijing who'd organized the You and Me experimental music festival earlier that year. Zhao Ziyi would later take on a deeper significance to me, but at the time he was still just a stranger. One of the members of the Shanghai Oscillator Group, Yu, was there as well — though I didn't recognize her at first. Fish played quite softly, then Zhao Ziyi played so soft as to border on silence. Finally they joined in a duet:

Side by side

You two stood, one

like a peach,

the other colored like

a freshly caught herring.

After they were finished, Xie Wang convinced Yu to play bass too. Unlike the soft discrete notes Fish and Zhao Ziyi played, Yu's bass emanated a slow all-consuming static.

I’d like to store my

soul in your bass amp,

dampening

each note you play for

eternity.

It turned out in the original incarnation of the Shanghai Oscillator Group (you see, there's all sorts of lore I didn't know about initially), it had been four oscillators, a guitar and a bass, rather than the five oscillators I'd seen at Trigger. Yu was the bassist, thus Xie Wang's request. After she played, I talked to her a little bit, added her Wechat, and a few days later mentioned I'd written that essay. This is how I ended up talking to the other members of group. Later on Yu and I would perform together several times as a duo.

I might as well use this as an opportunity to recount the history of the Shanghai Oscillator Group as I understand it, since they were a complete mystery to me back when I wrote that essay about them. I’d imagined that they were a group of avid collectors of vintage scientific instruments, meeting up once a month try out each others function generators. Perhaps the constant accumulation of these metallic boxes made them feel that they had to something with them. The only logical possibility was that they start a band. That was what I fantasized when I watched their first performance.

In reality, they began as workshop led by Mai Mai. 5 Oscillators, a guitarist and a bass — together they would perform one of Mai Mai’s compositions at an event on the Bund in October 2023. After the workshop ended, the guitarist left and Yu, the bassist, was inducted in as a full-time oscillator like the others. The performance I saw at Trigger, featuring five original compositions, was their second show. A Bunch of Noise was their third.

At A Bunch of Noise, Xiaoxiao held a big wooden frame wrapped in wire. Yu held a microphone. When they approached each other there was sharp loud feedback — though they had to get very close for it to work. Sometimes Xiaoxiao would attack Yu. Sometimes Yu would attack Xiaoxiao. Sometimes they would just wander through the audience, as people pushed and pulled each other to somehow alleviate the tension inherent in not wanting to be touched by these two abstruse figures, yet wanting still to gaze upon them, to try to understand what it is exactly that they were doing. Then the violence suddenly ended and they took to the stage with the rest of the oscillators.

Jet engines tucked

between your arms —

does the wind

on your face not

suffocate you?

After her performance, Yu complained about all the people in the Wechat group chat for A Bunch of Noise that had totally misunderstood her, characterizing her performance as homoerotic. I’d never joined the chat group, so I only have the vaguest idea of what they said. Maybe I missed out on an entire second dimension to the festival. I remember being amazed when I first got to China and discovered that every big event as a Wechat group associated with it, where participants can comment on/make fun of whatever’s going on in real time. Danmaku for reality. It seemed like my chance to experience whatever people are nostalgic for when they talk about using Pictochat at game conferences shortly after the release of the DS or early adopters of Twitter going crazy with it at South by Southwest. I quickly discovered that (1) I don’t have the guts to post in these public group chats and (2) no one else really seems to say anything worth reading. So I stopped bothering joining these kinds of groups.

During the break in the festival for dinner, Yu disappeared to eat with her friend Q. I stumbled upon Yifan, another oscillator whom I still didn’t know that well at the time. She was going to eat with Mai Mai and his little group, so I followed them to an outdoor Hotpot restaurant that Ah Ming had found for us. After we found a table, I noticed Han Han (AKA Gooooose) was with us. He sat down across from me and I wondered if I should tell him my girlfriend was a big fan of his (“She has the same haircut as you!”) but I decided against it. Mai Mai began talking about he had met Han Han on Soulseek in the “China room”.

“I’ve been in the China room!” I said. “No one ever replied to my messages though.”

Now, every time I open up Soulseek, I pop into the China Room and look the usernames listed in there. I wonder if one of them belongs to someone I know. I’ve yet to see someone ever post a message in there.

My favorite performance during A Bunch of Noise was probably the four-person improv session Shu Qi did with Toshio Mikawa (of the Incapacitants and Hijokaidan), saxophonist Wang Ziheng and drummer Li Ping. Digital met analog. Saxophone battled with drums. There weren’t any gimmicks. There weren’t any of the structures and forms that noise or free jazz sometimes borrow from conventional music in order to produce a sense of drama or momentum. There were just 4 “categories” of sound, pushing and pulling, touching and sweeping. It felt like what I, as someone who’s never actually watched sumo wrestling before, might imagine a four-way sumo match is like: four doughy bodies kneaded into one not-quite-human form. I was, in a sense, rooting for the home team: Shu Qi. I’d seen his moves in isolation and now they were being put to the test in hand to hand combat with three worthy opponents that I’d never seen in person before. As always, the resulting sound wasn’t the kind of thing one could put into words, but I wrote a poem anyways:

A pile of

batteries drained free

of their acid,

glittering beneath

the orange sunset.

Having listened to all sorts of permutations of strangers engaging in “free improvisation”, I still don't understand how my body can instinctually tell the difference between “that was amazing” and “that was lifeless”. There's no recourse to all the usual measures of “technical ability”. When all you have is “feeling”, it’s necessary to have absolute faith in yourself — not just as a performer, but as an audience member too. How else are you going to navigate this maze of undefinable sound?

The festival’s lead organizer was/is Mei Zhiyong, whose performances often consist of him battling with a metallic slinky-like snake which doubles as a sound source. He’s this big muscular guy, so the first time I saw him perform with the snake — the second to last set of the festival — I couldn't help but think of Laocoön and His Sons, which I’d spent many hours sketching over and over for an art class I took in college.

The last show of festival was the aforementioned "uterine sack": Laurent Lettrée's group ReD SignL played a noise accompaniment to the guy within dancing. It ended with Laurent screaming “Who wants more noise?!” and immediately starting up again, only for the sound guys to cut him off. People’d been yelling "encore" at the end of every other performance, but it was only Laurent of all people prepared to give them one.

After the festival was over there was a chance to “jam”. Yu had talked me into playing with her and her friend in a math rock band who’d brought a bunch of pedals. They wanted to try “ambient noise”. Yu said I could do vocals. Huang Lei got me a mic and handed it to me. Suddenly strangers materialized and tried to get me to give them the mic so they could scream into it in the most boring way possible. I let one guy do that, and he covered it with saliva. I didn’t let anyone else do it. I wanted to feel what it would be like to scream in a different way than those guys. So I tried that. I ended up not being able to talk for a week afterwards, and I probably scared Yu’s friend into never talking to me again. I was disappointed that I still just sounded like a guy screaming. Why couldn't I be some other creature screaming? Why did I always have to sound like myself?

I walked the streets looking for a bike. The Meituan app kept guiding me into alleys that, as far as I could see, were bikeless. I was moist with sweat that had dried and then been rehydrated in the cool midnight mist. It was a world just about to explode into green life again, though it hadn’t quite got there yet. By the time I did find a bike, I’d already resigned myself to my fate, so I kept walking the rest of the way. I got home around 1am and was greeted by girlfriend's dog Xiaohei. I took him for a walk. I took him to the Lawson across the street and bought a bottle of sparkling water, then when I got back I listened to Hang on the Box's song Shanghai and kept repeating the lyrics "fucking stupid city" to myself until I fell asleep.

After A Bunch of Noise, noise went back to being something I only saw in tiny rooms where 75% of the audience was other noise musicians. Compared to System, Trigger feels warm and safe to me, even if (or precisely because) the lighting gives one an impression of the cold professional office worker life. I always show up at least 15 minutes early so I can soak up the office building vibes, feel the plastic stools against my butt and disassociate as I stare down at the carpet squares on the floor, remembering all the good times when particularly violent performances loosened and displaced them. Waiting is a lot of the appeal of noise for me. The perfect performance would take an hour to set up and be done in 30 seconds. Everywhere else in the world of leisure I’m always on a time limit. If I’m in a practice room, then I’m paying by the hour and therefore don’t want to waste any time. When I’m at Trigger I’ve already bought my ticket. It feels like a practice room where I’m not obligated to actually practice. Ideally there would only be two or three other audience members, all strangers so I don’t have to talk to them. All the down time gives me a chance to think up my poems, which I usually don’t write down until I get home.

“As a kid, my mom would take me to funerals for people we didn’t know." This is something Stephanie told me once. "‘No one else is going, so we have to go,’ she would say. That’s how Trigger feels. A stranger is being cremated, and we all watch in silence as sounds fill the room. It’s a kind of meditation.”

What she was referring to was a performance from a week earlier by Black Stump (formerly known as LxVxTx), an Italian noise musician who's been living in Shanghai since the late 2000s. He'd used a video of a funeral in Nepal he'd taken with a telephoto lens, standing atop a distant mountain looking down at where the cremation occurred. When he's not performing, he shows up at events with his massive camera and crawls around to take black and white photos of people's hands in hopes of one day compiling them into a book.

I never went to funerals growing up, but I suppose I still can appreciate what Stephanie meant. I’ve often felt that noise has become a replacement for church for me. I went to a very normal protestant church with rows and rows of pews and a pulpit up front. I’d occasionally encounter people who’d go to “other” sorts of churches — churches that met in movie theaters, high school classrooms or in one case the upstairs of a poker parlor — churches with less than 20 members. I was always a little bit jealous of them. Why couldn’t I go to a cool weird underground church that has to meet in strange places? By the time I was old enough to go to any church I’d like, I’d already stopped believing in (or at least caring very much about) God. Thus, like many of my other childhood dreams, this easily attainable desire too became irrelevant. Seeing noise once or twice a week at one of the two places that regularly have noise shows — usually in the early afternoons — is the next best thing. I get to fit my body into a tiny room filled with strangers and acquaintances without needing to talk to them. As soon as the show begins, we are forced into a communal silence — except when Junky starts handing the mic to people and forces them to scream.

Back when I lived in America, the only Chinese noise performers I knew about were Yan Jun (who I didn't really listen to — I just liked his essays) and Torturing Nurse. The first album I heard by Torturing Nurse was NanaNanaNanaNanaNanaNana, and it’s still my favorite (I’m sorry if that’s a normie opinion). As far as I know, this was just Junky and Xu Cheng, who is no longer a part of Torturing Nurse, but still does solo work. The album hones in on precisely what I like about noise: screams and a large variety of vaguely electronic sounds. Sometimes they’re loud, sometimes they’re quiet. High frequencies and low frequencies. Sounds like instruments, and sounds like feedback. The vocals aren’t just screams either: there’s slurping, slobbering, blowing, sucking, moaning, whispering. All I could ever hope for is in there somewhere in one of these 47 songs of lengths ranging from 4 seconds to 2 minutes. I suppose the main point of comparison would be albums like Tokyo Anal Dynamite or Yellow Trash Bazooka by The Gerogerigegege, in the sense of being a procession of miniature experiences that are all “the same but different”, though I would say NanaNanaNanaNanaNanaNana feels a lot more “produced” and goes many more places.

Other albums I downloaded back in America included Hai Shangnurse, which features more long-form submerged screaming, S.A.R.S. with its dismembered drumming, and the guitars and yodel-like screams on Hate Human. These, it would turn out, were all very early albums. After I came to Shanghai, I learned that for nearly the past 10 years, Torturing Nurse had consisted of only Junky. Whenever I see videos of their old lineups, when they were a "they", for instance this performance at Li Jianhong’s 2pi festival in 2004 consisting of Junky, Misuzu, Miriam and Wan Jun, it feels like something out of another world. I’m sure there are plenty of people in that audience who to this day, when they hear the words “Torturing Nurse”, think of that rather than Junky contorting his body in a Keith Haring mask.

It’s really only through old Torturing Nurse albums that I’ve heard the noise side of Xu Cheng — whenever I’ve seen him perform solo, in his current “all-grown-up” form, it’s been more conceptual sorts of performances, e.g. talking to a cactus powered by AI, or having the audience all scan a QR code he’s displayed on a projector that adds you to a group chat.

Before Torturing Nurse, Junky was in the band Junkyard along with Misuzu, with whom he'd initially form Torturing Nurse with. The band has the strange distinction of being an intersection point with Ma Haiping and B6, two electronic musicians now known for very different kinds of music. Listening to Junkyard’s only full length album Junk & Retain Junk was the first time I felt like coming to China actually had any value. I of course could have listened to the album long ago back in America and I’m sure I would have it delightful had I done so, but instead I got to have the much more disconcerting experience of discovering this guy I’d encountered many times in tiny rooms had once, 20 years ago, together with several other guys who have since attained far greater mainstream “success”, made something absolutely amazing.

Over the many years that preceded Trigger's existence, one of the main platforms for noise was a roughly monthly gathering known as NOIShanghai (闹上海), which met at all sorts of different venues. The first NOIShanghai I attended was in July, 2023 at the Ming room. This is a "private study" in its owner Xie Wang's house. He started Ming Room as a Buddhist bookstore, which is still quite apparent from the selection available, but now he stocks whatever he finds interesting. In an interview, he said that putting on these noise shows was part of his self-cultivation: "These noise musicians can't play at bars. No one will listen. If I don't let them play at Ming Room, they won't have anywhere else to go."

This was NOIShanghai's second occurrence after the end of the pandemic (I'd missed the first one), and as such the room was packed. After the five sets that made up the show were over, I descended the steps of this ordinary residential building, walked aimlessly down Shaoxing road, passing by the entrance to the park. Later on I'd write this poem to commemorate the event.

My body still

contained faint traces

of caffeine

that afternoon you

crawled on top of me.

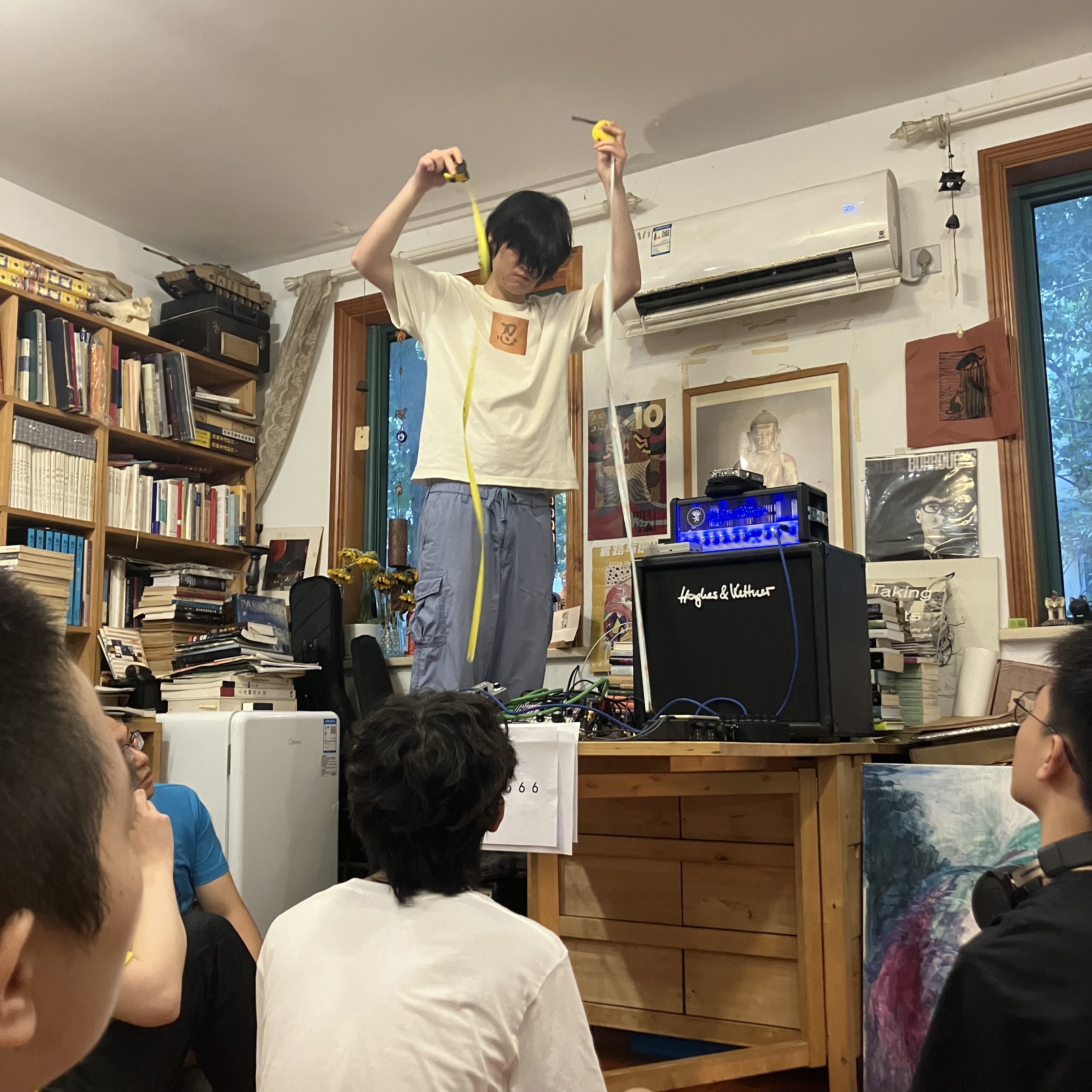

I was probably influenced by the Buddhist imagery that filled every corner of the Ming room, a "private study" containing all the books its owner, Xie Wang, has accumulated over the course of his life, stacked on tables and stuffed into shelves. When I saw the man standing on a stool shaking measuring tape around until it cut his skin or the other guy who, to the accompanient of a woman banging a drum and screaming, collapsed into a ball on the floor and starting shaking around like he was having seizure, then rolled himself over the audience and out the door, I couldn't help but think about the feebleness of our human bodies. This is the kind of lame story telling or meaning chasing I find myself engaging in whenever I witness something I do not and cannot understand.

I remember having a feeling somewhere between belonging and embarrasment that first time at NOIShanghai. I'd later on learn that the man with the measuring tape was Ding Chenchen AKA Noise 666, and the guy rolling on the floor was Junky. At the time though, they were just strangers to me. Despite buying a ticket to a publicly advertised event, I felt like an intruder, yet I hoped someday I'd be able to come again as a guest, through "the proper channels", whatever that meant.

NOIShanghai had started in 2005, a year after Torturing Nurse had been formed. To get an idea of what these early NOIShanghais were like, you can watch, for instance, this video from 2008. Later on NoiShanghai was able to consistently meet at 696 Live for a period of time, but after it closed they had to keep finding a different venue for each meeting. It was hard to convince normal livehouses and bars to host these kinds of performances though: tickets don't sell very well. Their setups weren't always suitable for noise and the bar owners sometimes didn't understand what noise as a genre even is. Just around the start of the pandemic, Ming Room started hosting performances, which gave them some stability.

I wrote a poem about that world I imagined, before I ever arrived in Shanghai:

Shrieks shimmering in

the oily darkness —

all I see

is swallowed up

by film grain.

Between May and October, there were around one NoiShanghai meetings a month at Ming Room, System and Yuyintang. As I write this, Ming Room is the only one of these places still around. I didn't realize it at the time, but when I entered this long-lived institution, it was already undergoing a massive life-cycle change. In October, Junky, the last remaining member of Torturing Nurse, along with Huang Lei, Shu Ride and Mei Zhiyong would open up Trigger on the third floor of the Lianhe office building in Putuo, just north of the Suzhou river. The idea was to have a venue in Shanghai similar to the Japanese venue Soup, dedicated entirely to noise and experimental music. They'd go from hosting at most one NOIShanghai a month, to hosting one or two shows a week, which they've been able to keep up for the past year and a half that it's been operating.

Not long after A Bunch of Noise ended, Junky started talking excitedly about an Italian artist who'd be coming to Trigger in May. This was Alessandra Zerbinati, as well as her collaborator Gyula Noesis. The two day event was, for me, the quintessential Trigger performance. It featured new custom designed procedures for us to follow: Before Zerbinati and Gyula’s set we all had to step outside into the hallway and check our phones in with Junky in order to ensure no one took any pictures. We waited for twenty minutes, phoneless. Every time I had my instinctual reaction towards boredom of reaching for my phone, I felt like some pathetic animal controlled only by a massive system of Pavlovian responses. The door suddenly opened, we stepped one by one into darkness and, as my eyes acclimated, there she was, crouching on plastic, naked:

It was me who

gathered each fiber

of your hair

from shipwrecked rope at

the bottom of the sea.

The next day featured several permutations of collaboration: Shu Ride and Rhythmic Shit played together, Torturing Nurse and Alessandra Zerbinati played together, but what I remember most clearly was Huang Lei DJing (sort of) while using his skinny body to wiggle and squirm around while Gyula Noesis emitted cries of pain in some combination of language and non-language, then came over and hugged Huang Lei, picked him up, and stuck his bleeding head up Huang Lei’s shirt. Huang Lei was in fact wearing a very special shirt: he had separate shirts for his Rhythmic Shit performance and his collaboration with Gyula Noesis. Before starting he’d realized he was wearing the wrong shirt. He tried to run out to the bathroom to change, but Junky and Shu Ride didn’t let him — for a brief moment he was shirtless in front of us all.

Unfortunately I didn’t write a poem that time.

At the end of June I got a message from Yu asking if I could go to Beijing in August. Zhao Ziyi had invited us to play at the You and Me Experimental Music Festival. When I’d first met Yu, she’d admitted to me that the greater part of her youth had been devoted to Xiangqi. As such she now harbored a deep antipathy towards the sport. This seemed to be the kind of emotion from which someone could make a few sounds out of, so in the month and half we had before You and Me, we agreed to go to the park once a week to practice Xiangqi in the shade, connecting the pieces to wires and letting them hiss.

When we arrived in Beijing we all slept on Zhao Ziyi’s floor. Back in Shanghai I suffered from insomnia each night. I’d lie sleepless on the mattress my girlfriend treasured so much that she’d gone through great expense to transfer it from apartment to apartment, despite them all already being furnished with mattresses. As I closed my eyes I’d feel endless vibrations (imagined?) pulling apart my flesh. The faintest sound of someone’s footsteps beneath our fourth floor window would pierce my ear drums. But that first night on the floor in Beijing while our new found roommates from Guangdong were up until 4am talking, I managed some of the deepest sleep I’d ever experienced.

Chess pieces bursting

into black flames —

A body made

of wires, plugged

into nothing.

Here is another poem about Yu.

I realize

now that your mouth

is hollow —

a scream this shrill,

embedded in glass.

Mai Mai arrived either the next day or the day after. He performed a piece with Xu Cheng that involved (randomly?) playing an instrument or reading some prepared writing. I forget the exact parameters that they were working in. I feel like this was a piece John Cage or some other famous conceptual musician had “composed”. "I am brimming with talent — whenever I sing, everyone stops and listens carefully." That's what I remember Mai Mai saying. As he spoke on stage to Xu Cheng’s accompaniment, so slowly, so solemnly, in a voice I couldn’t reconcile with the Mai Mai I’d conversed “in real life” with, I wrote down the following poem:

All along it

was this that you held

inside of you?

I heard it, I saw

it, lost in these faces.

I left Beijing a few days after this. I missed the last two days of the festival. I had to go to Jinan to visit my girlfriend’s parents. I missed the Zev Asher tribute show at Trigger too. I missed Xu Cheng reuniting with Junky, along with Huang Lei and the artist formerly known as Lolita Vibrator Torture. When I got back, the first show I saw was at Ming Room, where Junky played as Ultracocker Shocking, his “voice and body” alter ego, accompanying Yasu Ey. Before the performance started, Yasu gave out Kitkats to everyone.

So this is the

emissary we’ve waited

so long for.

Although he hardly speaks,

we can’t help but stare.

This was the performance that made me realize every single human being has a million other selves hidden inside of them. I'd seen Junky many times already, but the dance he'd done to accompany Yasu was like nothing else. Yasu sung like an opera singer, and Junky blew soundless air out of his lips like a fish, flopping on the beach. Instead of the Keith Haring pattern mask that Junky wore when he played as Torturing Nurse, Ultracocker Shocking donned a black mask.

The O that your mouth

makes when you whimper —

could I shrink

myself down and step

inside of it?

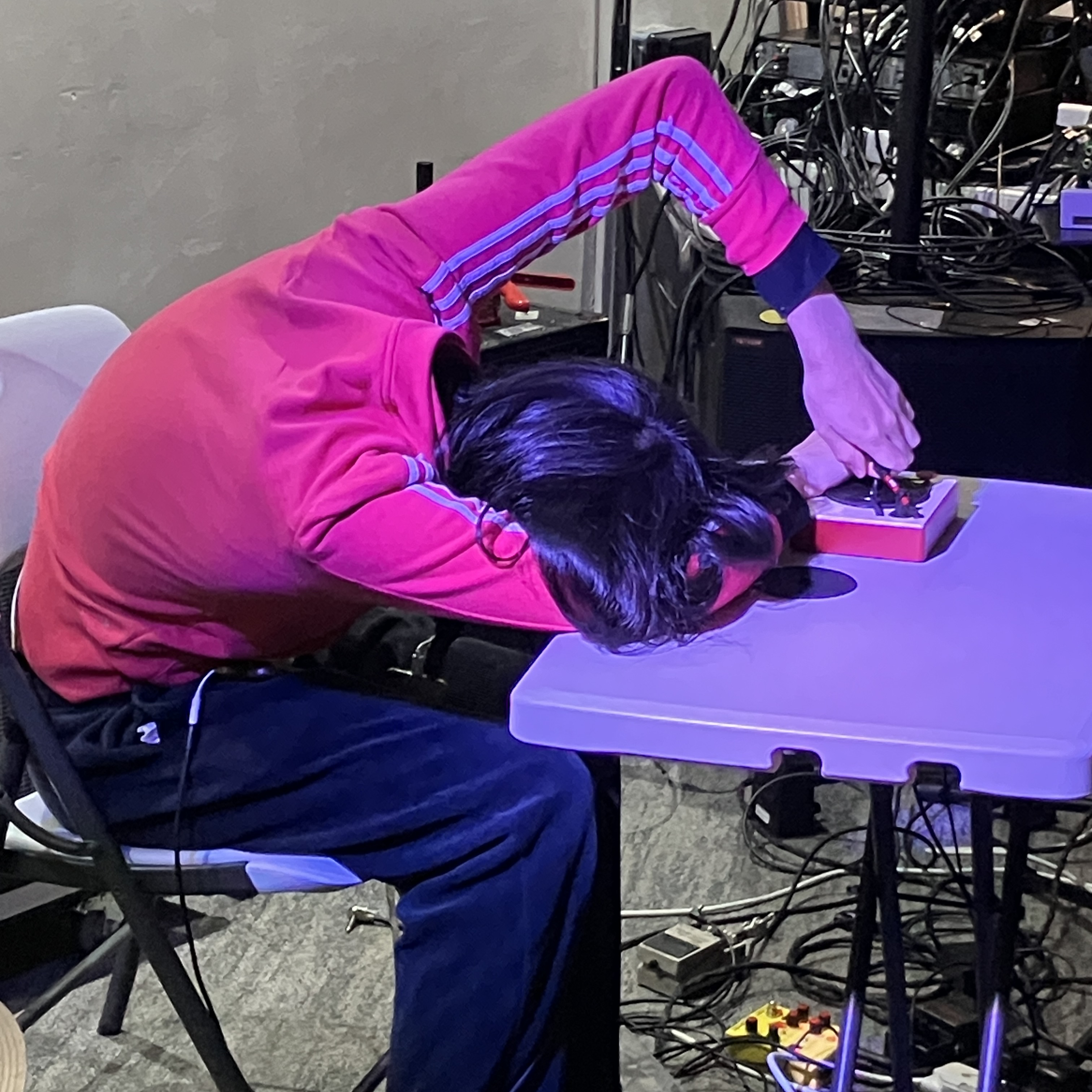

It’s a massive simplification based only on a few performances I saw over the course of one year of their multiple decades of activity, but I see Junky and Mai Mai as representative of two opposite poles of table-based-performances. Mai Mai sits behind a table and operates the equipment on top of it. Junky stands behind a table and bashes his whole body against it. We can come up with all sorts of silly metaphors for what this means. Maybe the rectangular pedals are all buildings in a city, and Junky putting his mask on represents the everyman becoming god, taking his rage out on the urban metropolis that mistreats and manipulates him in his everyday life, becoming the manipulator, forcing horrid sounds out of it. Somehow violent motions compel people to ascribe meaning to them, even if most of those attempts don’t hold much water as soon as you think about them for more than half a second. Mai Mai’s performances on the other hand don’t really compel that grasping for meaning — at least not for me. I’d like steal the phrase “suspension of belief” from my girlfriend’s friend Simon, who used it when I was talking with him about Mai Mai. (I was going to write “my friend Simon”, but somehow I feel like I’d offend him by insinuating that we’re friends.) Unlike many of these guys who calmly sit behind a table and make electronic noise for half an hour, somehow Mai Mai manages to make one half of your brain forget that you’re just sitting on a plastic chair in a brightly lit room next to a bunch of other people gazing seriously at him. He has something important to tell you, and despite the fact that electronic noises are a medium completely incapable of expressing whatever that important something is, he's going to do his best anyways to say it.

Plastic stools

weighed down by strangers

blocked the door —

thus my bladder was

forever deformed.

I wrote this at Trigger one afternoon when Mai Mai and Zhu Songjie were playing guitar feedback. I'd gotten to Trigger early and managed to drink a whole bottle of water and cup of coffee before the show ever started for reasons I don't comprehend now. Very quickly I had to pee. Halfway through their performance, I was on the threshold of insanity. When I read this poem now, I remember the absolute panic I felt every time I thought the guitar feedback was dying down only for a new texture of guitar feedback to suddenly swell out of the decay, like a new theme in a Bach fugue, introduced so that it might interact with all the themes that came before.

"This could go on forever!"

I kept looking to my left at the door wondering how I was going to get past the sea of people in my way. The second Mai Mai and Zhu Songjie looked at each other in agreement then made the little head nods towards the audience that indicate the performance is over, before the applause had even finished I stood up and leaped over the heads of the people sitting on their stools, then dashed to the bathroom. Even after evacuating as much urine as I possibly could out of myself, my bladder still seemed to contain a strange pressure that was alien to me. As I contemplated this, Mai Mai suddenly materialized at the urinal next to me. He mumbled some kind of greeting to me. For a moment I felt like we were in the same club — two people who really had to pee. I washed my hands and went back to the room, amazed at how wonderful life could feel with an empty bladder.